Timber licences, lot surveys and access roads put Lost Lake at risk

By the early 1960s the impending expiration of timber licences that straddled Alta Lake catalyzed a rapid shift from industrial forestry to potential waterfront subdivision: developers began staking lots, preparing applications for waterfront property, and extending logging roads that would have permanently altered shoreline access and ecosystem corridors around Lost Lake.

Immediate threats: mills, logging corridors and residential subdivision

Throughout the 1940s and 1950s the area had already been transformed by the Great Northern Mill on the north shore and by broadscale logging of adjacent forest stands. Those industrial infrastructure elements—mill access, skid trails and primitive roads—created a transport matrix that made rapid residential conversion feasible once timber tenure expired. Local planners at the time lacked the municipal regulatory framework to block waterfront parcelization: the Resort Municipality of Whistler (RMOW) would not exist for another 15 years.

Community defenders and technical advocacy

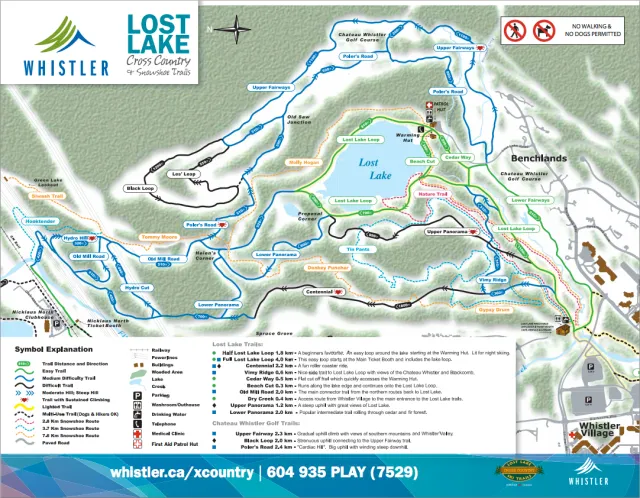

The campaign to secure Lost Lake as municipal parkland was coordinated by a network of volunteer conservationists and public-sector foresters who combined ecological arguments with land-use logistics. Key interventions included negotiating the reassignment of timber licences, using contacts within provincial parks administration, and physically mapping trails and public access points to demonstrate the site’s recreational value versus private-development potential.

Don MacLaurin’s role: practitioner, educator and negotiator

Don MacLaurin (1929–2014) emerged as the pivotal figure in that process. A forester with the BC Forest Service and later an instructor at BCIT, MacLaurin leveraged technical expertise in forest management and park planning to bridge the divide between industry stakeholders and community recreation interests.

- He used professional networks within provincial parks to advance designation options.

- He traced and documented access routes and trail corridors to defend public access.

- He campaigned publicly and privately to reassign threatened timber licences away from clearcutting and subdivision.

MacLaurin’s pragmatic approach—evaluating both economic and ecological trade-offs—helped shift regulatory and market incentives away from shoreline privatization. His experience in forestry and parks management equipped him to advocate for legal protection and to anticipate the logistical requirements of managing an accessible municipal park.

How the park designation unfolded

Lost Lake Park was officially opened in 1982 after a sequence of administrative and civic actions: timber licences were moved or allowed to lapse without conversion to private parcels, trail networks and signage were proposed to anchor public use, and municipal structures were created to manage toad migration and ongoing stewardship. The result preserved continuous public shoreline and protected woodland corridors.

| Year | Key event | Logistical impact |

|---|---|---|

| 1930-talet | Rainbow Lodge guests use Lost Lake for recreation | Informal access established from existing lodges |

| 1940s–1960s | Great Northern Mill and logging operations | Industrial transport network constructed |

| Tidigt 1960-tal | Developers survey waterfront lots as timber licences expire | Threat of shoreline privatization; increased demand for municipal planning |

| 1982 | Lost Lake Park officially designated | Public access secured; recreational and conservation infrastructure implemented |

Local stewardship and ongoing management

Once protected, Lost Lake Park became the focus of practical stewardship measures that required logistical coordination: permanent signage, seasonal fencing, and even specially engineered underpasses to support Western Toad migration. The RMOW developed staff expertise and operational protocols to manage visitor access while protecting amphibian corridors during migration peaks.

Historical context: from Rainbow Lodge to conservation victory

Recreational use of Lost Lake predates its industrial phase. In the 1930s guests at Rainbow Lodge were taken to the lake for swimming, fishing and picnics; the area’s social value as a day-use destination contrasted sharply with the post-war forestry economy that dominated mid-century land use.

The shift from recreation to industry and back to preservation mirrors broader patterns in North American mountain resorts where transport infrastructure—logging roads, mill spurs, and later municipal service roads—often become the catalysts for either development or protection, depending on policy choices and the presence of engaged advocates.

Other conservation wins tied to the same advocacy network

MacLaurin’s influence extended beyond Lost Lake. He advised RMOW efforts to prevent clearcutting on the south side of Whistler Mountain and advocated for the protection of the Ancient Cedars north of Whistler, leveraging both technical mapping and civic persuasion. Trails such as those in the Whistler Interpretive Forest owe their alignment and interpretive messaging to his planning work. The suspension bridge over the Cheakamus River bears his name—MacLaurin’s Crossing—a physical reminder of his role as a connector of people and landscapes.

Key lessons for destination and tourism planning

- Infrastructure shapes futures: Logging roads and mill operations can expedite either development or access for conservation, depending on land tenure decisions.

- Technical advocacy matters: Forest management expertise and trail mapping lend credibility to preservation arguments with regulators and the public.

- Community stewardship reduces management costs: Volunteer programs and targeted mitigation (e.g., amphibian underpasses) create durable protections for both species and recreation.

For destinations that host lakes, beaches or forested recreation areas, the Lost Lake story is a case study in how transport corridors and tenure expiry create narrow windows for decisive planning that favors public access over privatization.

In summary, the survival of Lost Lake Park came down to a combination of timely administrative maneuvers, technical forestry and parks expertise, and sustained civic advocacy led by figures such as Don MacLaurin. The park’s preservation insulated shoreline access from subdivision, redirected former industrial transport networks into trail systems, and established long-term stewardship practices—measures that continue to protect wildlife and deliver recreational activities on the lake for visitors and residents alike. GetBoat is always keeping an eye on the latest tourism news and developments such as this, tracking how decisions about land, water and access influence broader destination planning, boating and water-based activities, beach use, fishing and recreational use of lakefronts. GetBoat.com

How Lost Lake Park was saved from private development">

How Lost Lake Park was saved from private development">